Merlin

General Description

Merlins are small, compact falcons. Three subspecies are found in Washington. The Black Merlin is solid black on the head and back, and dark with a minimal amount of light streaking on the breast. It has a white throat patch. The Taiga Merlin is lighter in color than the Black Merlin, with a bluish-black back, a white eyebrow line, and white bars across the tail. The Prairie Merlin is lighter in color than the other two.

Habitat

Merlins breed in rugged terrain that provides both trees for nests and open areas for hunting. In Washington, they can be found in very small numbers near openings in coniferous forests in the Puget Sound area, along the Cascade crest, and at other high-altitude areas in the North Cascades and in northeastern Washington. During migration and winter, they are found in more diverse habitats, including coastal areas, estuaries, agricultural lands, and suburban towns

Behavior

Merlins capture airborne prey, employing a level sprint with abrupt turns. Rarely do they use the steep dive technique for which their larger relative, the Peregrine Falcon, is well known. They cache extra food on a branch or in an unused nest. Sometimes they fly low to the ground, surprising their prey. Merlins practice a variety of acrobatic, in-flight, courtship displays. They are cantankerous birds, seldom passing up a chance to hassle another raptor.

Diet

Small birds make up the majority of the Merlin's diet. Rodents, bats, and reptiles are also taken, as well as large insects such as dragonflies, which are especially hunted by fledglings in the late summer. Coastal Merlins take advantage of large numbers of migrating shorebirds during the fall and winter. Starling flocks often attract Merlins.

Nesting

Merlins are monogamous. The female typically lays 4-5 eggs and does most of the incubation. The male provides the female with food, and takes over incubation duties while she eats. When the young hatch, the female broods and the male hunts. He brings food back to the female, who in turn, feeds it to the young. Both parents help rear the young. Merlins usually use other birds' old nests, or rarely, a natural cavity. They mainly nest in conifers between 18 and 36 feet high in cities, or, in open prairie, in old crows' nests.

Migration Status

The Black Merlin subspecies is generally non-migratory, but the Taiga Merlin migrates south from Canada into the US, Central America, and northern South America. Females head south ahead of the males, typically in mid-August. In spring, males arrive ahead of the females. Merlins migrate during the day, but may begin to move up to two hours before dawn, and thus are often missed in migration counts and hawk watches.

Conservation Status

Previously there was concern that the population had been negatively affected by pollutants, but it has recently been shown that no changes in abundance have been recorded over the past 40 years. Some evidence indicates that wintering populations may actually be increasing, due to increased breeding success in the north. Habitat loss and potential loss of wintering grounds (for migrant populations) are potential concerns. The status of the Black race is not well known, since it is one of our rarest and most elusive nesters.

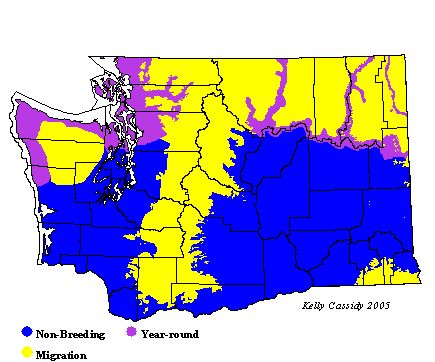

When and Where to Find in Washington

The Black Merlin is a very rare breeder in coastal forests along the outer coast of the state, the Hood Canal area, and Puget Sound. The Taiga Merlin is a very rare breeder in high-elevation forests of the north Cascades and northeastern Washington where boreal conditions exist. Prairie Merlins occur in the state, passing through in migration. Merlins are commonly found throughout western Washington, including urban areas, in winter and during migration. In eastern Washington, Merlins are uncommon in winter and during migration.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | U | U | U | R | R | R | U | U | U | U | U |

| Puget Trough | U | U | U | U | U | R | R | U | U | U | U | U |

| North Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| West Cascades | U | U | U | U | R | R | R | R | U | U | U | U |

| East Cascades | U | U | U | U | U | U | U | |||||

| Okanogan | U | U | U | R | R | R | R | R | U | U | U | U |

| Canadian Rockies | U | U | U | U | R | R | R | R | U | U | U | U |

| Blue Mountains | R | R | R | R | R | |||||||

| Columbia Plateau | U | U | U | R | R | U | U | U |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map