Great Horned Owl

General Description

Great Horned Owls are large, powerful owls with prominent ear-tufts, prominent facial disks, and bold yellow eyes. Their plumage is a mix of mottled brown with white-and-black barring, with some white at the throat. There is much variation in the darkness and shade of these colors across their range.

Habitat

Great Horned Owls are supreme generalists. They are found in more varied habitats than any other owl in North America. They often use wooded habitats, especially during the breeding season when trees or heavy brush provide cover. However they also nest in cliffs in arid areas far from trees. Their preferred habitat is open or fragmented woodland with treeless areas nearby.

Behavior

Like most owls, Great Horned Owls have keen hearing and keen vision in low light, both adaptations for hunting at night. These aggressive and powerful hunters most commonly use a sit-and-wait approach, watching from a perch and swooping down on passing prey to seize it with their talons.

Diet

Great Horned Owls are opportunistic generalists, taking advantage of whatever prey is available. They have the widest prey base of any North American owl. In most places, most of their food consists of mammals such as rabbits, skunks, and large rodents. They also eat a variety of birds, including grouse, coots, and several other species of owl. To a lesser extent, Great Horned Owls also take reptiles, amphibians, fish, and even large insects.

Nesting

Great Horned Owls are early nesters and begin calling in courtship in early winter. Monogamous pairs form long-term bonds. Though they sometimes nest in caves or on cliff ledges, they most often nest in deciduous trees. Great Horned Owls do not build their own nests, but use nests built by hawks, crows, magpies, herons, or other large birds. Most are abandoned nests from previous years, but Great Horned Owls also take over active nests. They add no new nest material. Since nesting typically begins in late January or February, before trees begin to leaf out, Great Horned Owls on the nest can often be seen easily. The female incubates 1-4 eggs for 30-37 days while the male brings her food. The young remain in the nest for about 6 weeks, then climb out onto nearby branches. They begin taking short flights at 7 weeks, and can fly well at 9-10 weeks. Both parents feed and tend the young for several months, often as late as September or October.

Migration Status

Great Horned Owls are not considered migratory. Northern birds, however, may wander long distances in the fall and winter.

Conservation Status

Great Horned Owls are widespread and common. They adapt well to change and are doing well in most areas. The Breeding Bird Survey recorded a significant increase in Washington since 1966. As more of Washington's forests are fragmented by logging, more area becomes available for Great Horned Owls, sometimes at the expense of endangered Spotted Owls, which not only require old-growth forest but also are preyed upon by Great Horned Owls. The Spotted Owl is not the only Washington owl that has been affected by expanding Great Horned Owl populations. In eastern Washington, Great Horned Owls displace Barn Owls in old buildings and barns.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Great Horned Owls are common throughout most of Washington year round. Two subspecies of Great Horned Owl nest in Washington, one on each side of the Cascade Mountains.

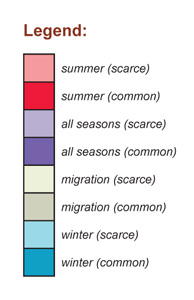

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Puget Trough | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| North Cascades | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| West Cascades | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| East Cascades | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Okanogan | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | C |

| Canadian Rockies | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Blue Mountains | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Columbia Plateau | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Flammulated OwlOtus flammeolus

Flammulated OwlOtus flammeolus Western Screech-OwlMegascops kennicottii

Western Screech-OwlMegascops kennicottii Great Horned OwlBubo virginianus

Great Horned OwlBubo virginianus Snowy OwlBubo scandiacus

Snowy OwlBubo scandiacus Northern Hawk OwlSurnia ulula

Northern Hawk OwlSurnia ulula Northern Pygmy-OwlGlaucidium gnoma

Northern Pygmy-OwlGlaucidium gnoma Burrowing OwlAthene cunicularia

Burrowing OwlAthene cunicularia Spotted OwlStrix occidentalis

Spotted OwlStrix occidentalis Barred OwlStrix varia

Barred OwlStrix varia Great Gray OwlStrix nebulosa

Great Gray OwlStrix nebulosa Long-eared OwlAsio otus

Long-eared OwlAsio otus Short-eared OwlAsio flammeus

Short-eared OwlAsio flammeus Boreal OwlAegolius funereus

Boreal OwlAegolius funereus Northern Saw-whet OwlAegolius acadicus

Northern Saw-whet OwlAegolius acadicus