Red Phalarope

General Description

Female Red Phalaropes in breeding plumage have deep rufous necks, breasts, and bellies, and brown and black mottled backs. Their heads are black with white cheeks, and their bills are yellow. Males in breeding plumage look similar, but are duller, with a brown rather than a black cap. The adult in non-breeding plumage looks similar to a Red-necked Phalarope in non-breeding plumage, with white below and light gray above, a white head, and a black ear patch behind the eye. The Red-necked Phalarope's back is streaky gray, however, and the Red Phalarope's back is unstreaked. Juveniles have buff-colored underparts and heads. Their backs are black, edged in buff. The Red Phalarope's bill is much thicker than those of the other two species. The bill is yellow in breeding plumage, and dark with a lighter base in non-breeding plumage. The Red Phalarope has short legs and lobed toes. All adult plumages show a distinct white stripe down the wing and a dark stripe down the tail, with contrasting color on the sides of the rump. This species is also called the Gray Phalarope.

Habitat

The Red Phalarope spends more time at sea than any of the other phalaropes. It nests in the low, wet tundra of the high Arctic coasts. Outside of breeding season, it is usually at sea, wintering in the waters off western South America and Africa, but also as far north as western North America. It is rarely found on fresh water, but when it is, these are typically small bodies of water, such as sewage ponds. Red Phalaropes usually occur farther offshore than Red-neckeds, but there may be an overlap. They can often be found in areas with upwellings or convergence zones that bring food to the surface.

Behavior

Red Phalaropes are usually in smaller flocks than Red-necked Phalaropes, but are sometimes in mixed flocks with them. They are often found with whales, and will pick parasites from their backs. These active birds generally feed by picking food from the water's surface, but will also strain plankton through their bills. When swimming, they occasionally spin in tight circles and create upwellings of food. They may land on seaweed mats at sea. When they are driven ashore by storms, they forage by walking slowly along the water's edge.

Diet

On their breeding grounds, Red Phalaropes eat a variety of invertebrates, especially insects, mollusks, and crustaceans. Their winter diet on the ocean is not well known, but includes small aquatic creatures.

Nesting

The female attracts a male with a display flight. Both sexes start scrapes, and the female picks one. The male adds a lining of grass, lichen, and moss to the shallow depression concealed in low vegetation near the water. After laying four eggs, the female leaves the male to provide all parental care. He incubates the eggs for 18-20 days and tends the brood once they hatch. The young leave the nest within a day of hatching and find their own food. The male may leave the young within a few days, or may stay with them until they can fly, at 16-18 days.

Migration Status

Red Phalaropes don't stage at interior lakes as do the other two phalaropes. They head for the ocean as soon as they have finished breeding. Most of the migration occurs offshore as well.

Conservation Status

The Canadian Wildlife Service estimates the global population of Red Phalaropes at 1,000,000 birds. This species is abundant on its breeding grounds, but is threatened by oil spills at sea and potential development of its breeding habitat.

When and Where to Find in Washington

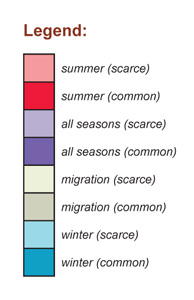

A pelagic boat trip, especially during migration, is the best way to see Red Phalaropes. Red Phalaropes are the least common of the two ocean-going phalaropes, seen about half as often on boat trips as Red-necked Phalaropes. They can sometimes be seen from the coast, or even on shore in puddles and ponds, after a storm. They are late migrants, and commonly stay in the waters off Washington until December. Juveniles are very rarely reported in eastern Washington in the fall. Offshore, they can be seen in any month of the year, but are rare for much of that time. Spring migrants start coming through in the beginning of May, and are common by the second half of May. The spring migration is condensed, and birds are uncommon by the beginning of June. They become common again in mid-July, as adults start migrating south, and they remain common into mid-November, as the young of the year follow the adults. They are still present, but uncommon, until the end of November, after which they become rare again until spring.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | U | U | R | U | U | U | U | R | R | |||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | R | R | U | U | R | R | U | U | U | R | R |

| Puget Trough | ||||||||||||

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | ||||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria

Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes

Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes Wandering TattlerTringa incana

Wandering TattlerTringa incana Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca

Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca WilletTringa semipalmata

WilletTringa semipalmata Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes

Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda

Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda Little CurlewNumenius minutus

Little CurlewNumenius minutus WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus

WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis

Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus

Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica

Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica

Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa

Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres

Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala

Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala SurfbirdAphriza virgata

SurfbirdAphriza virgata Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris

Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris Red KnotCalidris canutus

Red KnotCalidris canutus SanderlingCalidris alba

SanderlingCalidris alba Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla

Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla Western SandpiperCalidris mauri

Western SandpiperCalidris mauri Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis

Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis Little StintCalidris minuta

Little StintCalidris minuta Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii

Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla

Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis

White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii

Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos

Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata

Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis

Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis DunlinCalidris alpina

DunlinCalidris alpina Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea

Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus

Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis

Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis RuffPhilomachus pugnax

RuffPhilomachus pugnax Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus

Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus

Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus

Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata

Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor

Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus

Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius

Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius